Is the cyborg mountaineer still an artist?

More than a century ago, George Mallory wrote that adventure qualifies as art. Is that still true today?

For those of you who prefer to read on paper (or e-reader) rather than in your Substack or email app, I have converted this essay into an easily printable PDF file.

In 2022, fastpacking across the Alps in a very modern ultralight style and fully dependent on my smartphone, I felt… hollow.

Modern ultralight backpacking decrees that thou shalt use thy smartphone for every little thing. It’s the ultimate multi-use item, and the logic of ultralight raises multi-use items onto an unassailable pedestal. Paper maps? Hard to justify when a phone can store as many maps as you need. Camera? Phone cameras are great! Entertainment? You’ll never be bored again! You get the picture.

It’s so easy to succumb to this logic. Why would you carry dedicated items when the smartphone can do it all? Older approaches to lightweight backpacking advocated a more cautious approach, urging the wanderer to consider factors such as the consequences of a tech failure. But the tech has matured. Smartphones are waterproof, rugged, and long-lasting now. The cameras are great. You can still make a safety argument for paper maps if you want, but the reality is that thousands of hikers use digital maps in perfect safety.

So the arguments in favour of just using your phone for everything look pretty tempting, and I get it, I really do – it’s the default now. It’s what we all do every day. Why should the trail be any different? Why should some of the most intense and personally meaningful experiences of our lives be given special treatment – especially when there are so few practical arguments to the contrary?

Back to my Alps traverse in 2022. I was tapping out daily journals in my phone’s notes app, but I was also posting stories and reels to Instagram (for good reason; it was part of a brand project we were doing at Sidetracked). Constrained by the need for an ultralight load and a tiny pack, I couldn’t bring a dedicated camera either, so I was also using my phone for pictures. Maps too, although day-to-day navigation was mainly handled by a do-everything Garmin smartwatch that I followed for hundreds of kilometres, no thinking required.

Two weeks in, I typed:

I wish I’d brought a real paper journal instead. Somehow the experiences are more indelibly ingrained when I write them down on paper. Somehow the feelings are only my own when I have my own space to process them, and this black rectangle in my hand is not my own space.

It was a glorious journey – one of the most amazing of my life, travelling fast and light across my beloved Alps, finishing in Zermatt. A real emotional roller coaster. And yet I could not shake the nagging sensation that the emotions were somehow not mine. Looking back, even the photos I took were so clearly captured in order to fit specific ideas for Instagram stories.

Reading through the text file I typed on my iPhone during that trip, I’m surprised by the concluding remarks:

Meanwhile, the Matterhorn watches over me. A much younger me once gazed up at this strange old rock and dreams were kindled in the mind’s eye. Those dreams have shaped my life and will continue to do so far into the future.

The conclusion of my journey in Zermatt was an emotional moment. And yet those words did not originate in my trail journal. They originated in an Instagram story I posted while wandering the streets of Zermatt late at night, reflecting on the greatest adventure of my life, marvelling at the tides of fate that had brought me back to this place after so many years. The narrative was neat. Maybe too neat.

So was the thought mine, or was it imposed upon me by the shape of the machine through which it had been broadcasted? What impulses shaped it?

Was the emotional arc of the entire journey mine?

And if not, what was it?

Human experience and art, creativity and adventure have been cast in a new and strange glow now, with the very existence of AI whittling away at the edges of our humanity. We retreat into a kind of ever-diminishing god of the gaps until we must ask ourselves what, if anything, is truly ours.

This also applies to our adventures out there in the mountains. To the experiences that, to all outward appearances, are the most human of all.

I believe that adventure quite literally is art. Whether or not you create anything based on it is beside the point; the experience itself, at least when unmediated, is a complete work of art. More than a century ago, in his celebrated essay ‘The Mountaineer as Artist’, George Mallory wrote:

A day well spent in the Alps is like some great symphony. Andante, andantissimo sometimes, is the first movement – the grim, sickening plod up the moraine. But how forgotten when the blue light of dawn flickers over the hard, clean snow!

[…] every mountain adventure is emotionally complete. The spirit goes on a journey just as does the body, and this journey has a beginning and an end, and is concerned with all that happens between those extremities. […] The glory of sunrise in the Alps is not independent of what has passed and what’s to come; without the day that is dying and the night that is to come the reverie of sunset would be less suggestive, and the deep valley-lights would lose their promise of repose.

We respond emotionally to art because we know we are mortal and will die one day. Memento mori. In this short span between my fingertips on the crystal edge and these tense feet cramped on the crystal ledge I hold the life of man and all that.

Mallory also asserts that the human flow of memory and time are crucial to the formulation of this experience, and therefore this great artwork of mountaineering (by extension all human adventure). To me this intuitively makes sense; an emotional journey is by definition a narrative. But we have to experience this on a human scale.

Does the spirit still go on a journey when it’s been boxed up into Instagram stories? How can it? The world of the smartphone exists outside of time and space. The object itself is a hypermassive black hole. A mirror. Nothing on its surface is permanent; images flash by at lightning speed, hypnotising us. The images are composed of insubstantial light, not matter. And it slips through time like oil. By communing with it our minds ease into the datasphere, growing larger and more capable in many respects but also so very diffuse. The world of the smartphone – perfected corporate consumerist capitalism – is the antiworld to that of adventure, of rich unmediated human experience.

The only journey being facilitated by the mirror is the spasmodic flitting from one performance to the next, one purchase to the next. We grow old and simplified just looking at it. It does not empower us; it digests us. It is the void.

Art, as any painter knows, requires deep looking. The painter must observe not only form, shade and hue but also the gestalt of the thing being observed. This is why personal sketches, made in the moment no matter how briefly, so often recall a scene with more life than any photograph. We looked more deeply; we felt and experienced more deeply. That – experiencing it and then communicating it to another human being – is art.

But as I discovered in the Alps in 2022, mediating my experience so intensely through the black mirror of the iPhone stripped out all that. When I think in reels or stories or tweets or whatever I am not really thinking or feeling, and therefore not experiencing; I am performing, because that is all the machine knows. Even when typing private thoughts in the Notes app, the incentives don’t line up. A smartphone is engineered to steal your attention away from the physical world and the flow of time. It eats time and physical experience; these are the things that feed it. How, then, can one possibly experience a rich inner emotional experience with any degree of authenticity when everything is mediated by the mirror?

Years later, I still look back on my Alps fastpacking journey and feel strangely disconnected. The events are all there in my head, but they don’t quite line up. I don’t feel quite like me. The same, curiously, is true for other big trips I’ve done in a smartphone-heavy style over the years. I was there, but somehow I also… wasn’t.

This isn’t just about social media any more, is it? It’s about what we choose to give our attention to during these great, soul-defining moments. Give all our attention to an experience-eating black rectangle of glass and our thoughts, emotions, and ultimately our deeds will be constrained by that shape. Not just now but in our memory forever.

Give all our attention to tools and methods that make our attention grow – that tease us out of ourselves, that help us look and feel more deeply while connected to the natural world – and perhaps the mountaineer can still be an artist even if they’ve never painted a picture in their life. The art lives in the soul, and when it does so we know we are still human after all. When we make this art we assert that we can still look away from the void whenever we goddamn choose, no matter the incentives or the forces arrayed against us.

Perhaps the story of pretty much every adventure is simply this: I am alive.

What is the story of a day spent looking at a phone? I am consumed.

In practical terms, what am I actually advocating here? I’ve never pretended to have all the answers, and I doubt I ever will. All this is so personal. My theories and beliefs change from year to year.

I’ve long since admitted that it’s no longer practical for me to live my life without a smartphone. So I’m not advocating smashing it with a rock or anything like that.

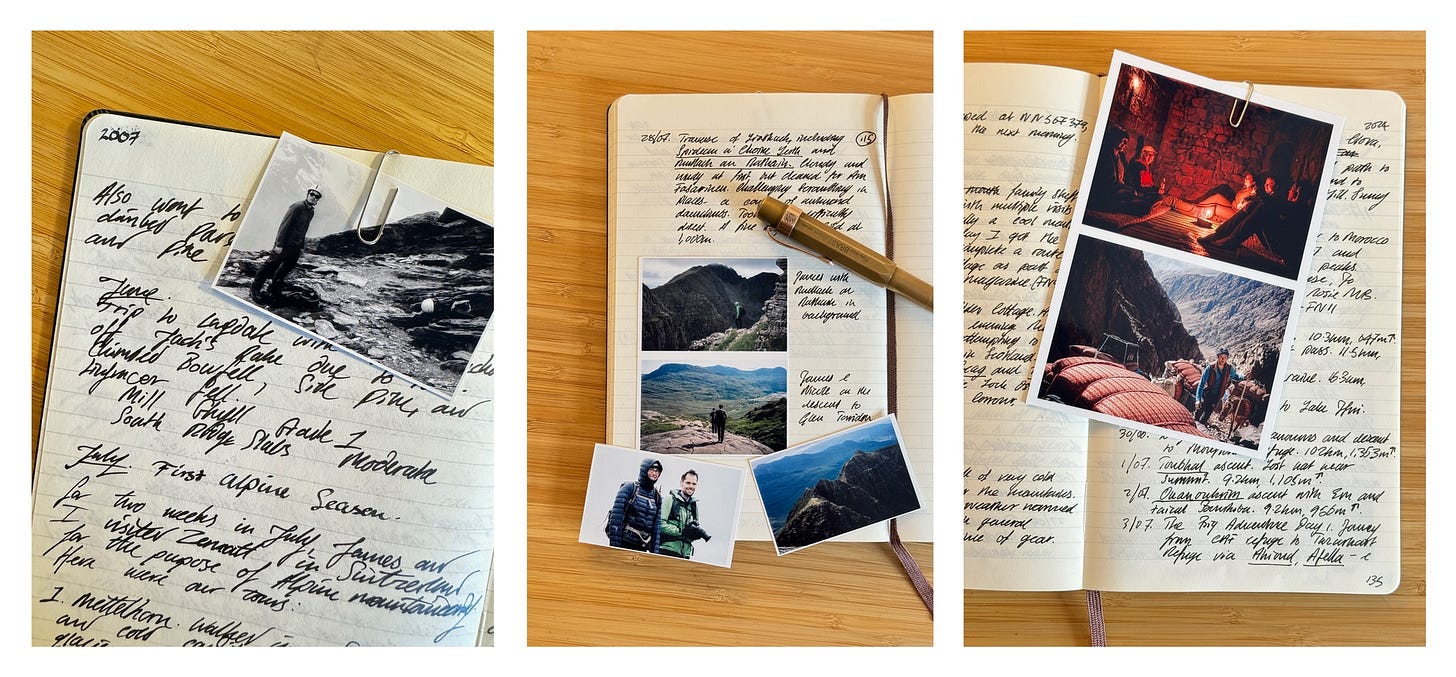

All I can say is that my fundamental baseline is to make sure I’m not using my smartphone for everything on a big backpacking journey. I will never conduct another big trip without a paper notebook in which to write my journal. Framing my thoughts on paper is, for me, absolutely vital in order to actually experience what I’m doing in the context of real space and real time.

I will never again do a trip like this with access to social media. (I wrote an entire book about this so won’t go into it all again here now.)

I’ve also gone back to paper maps; again, it’s about anchoring experience spacially to physical objects. Traditional navigation requires one to be more present and attentive, while navigating with a smartphone makes one less so. I’ll have more to write about this in future.

I guess what I’d like to see is the modern ultralight backpacking community adopt a more nuanced approach to the tools and methods we advocate. Rather than saying ‘just use your phone, bro’ when someone asks for advice about a gear list for a big trip, why not think for a second about why people do this stuff?

There are people out there who trek across continents just to get likes on Instagram. I have met some of these people (they’re awful). But I like to think that most of us still do this because we want to feel something.

Maybe it’s time to change the messaging and inject a bit more humanity back into all this. Uncertainty, too, perhaps. Adventure needs jeopardy just as art needs imperfection. Maybe we can learn from older, pre-digital methods of lightweight backpacking. Few of us, after all, go as light as Ray Jardine once did, and that was in the pre-internet era.

So bring along your notebook, paper maps and big camera if you want to, and who cares if your base weight goes up by 500g? Are you doing this to impress people on the internet or get your pack down to an arbitrary pack weight? Why are you doing it? Ask yourself that question. Answer it.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that many people in the world of adventure are quite literally artists. Climbers, long-distance backpackers, mountaineers and bikepackers are so often also writers, photographers, drawers and painters. When we experience the art of life, we can’t help but create.

I’ve been a writer all my life, and a serious photographer for over a decade. When I was much younger, I was also passionate about drawing.

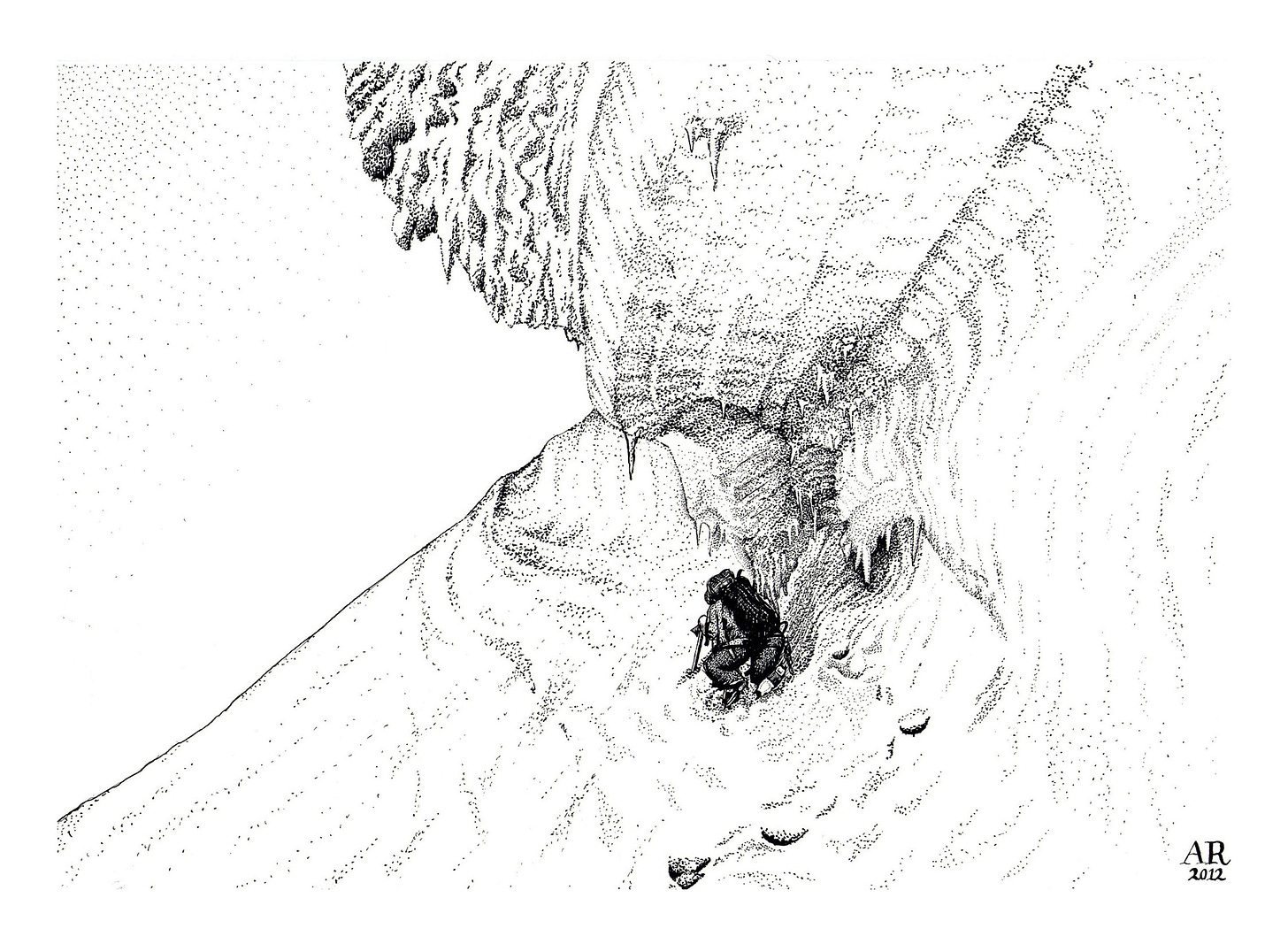

In recent months I’ve felt the urge to pick up my pen once again. Sometimes when I’m out on the hill I’ll sit for an hour and look – really look – at the scene in front of me, rendering it in ink on the page instead of a fleeting moment imprinted on photographic film.

The results are clumsy and imperfect as I gradually recover old skills. But that doesn’t matter. It’s the very act of being there, looking, my experience totally unmediated, that counts – and it changes my experience of the trip afterwards too, impressing it deeper and more richly in my memory.

Art doesn’t have to be perfect or even good in order for it to have value. Art is in the doing, and it’s the experience that counts. The same is also true of adventure.

If you like what you've read, please subscribe to receive updates in your inbox and Substack app. Thanks for your support. And if you've enjoyed what you have read, please tell someone else about it!

All images © Alex Roddie and James Roddie. Images produced using a camera and free of AI contamination. All Rights Reserved. Please don’t reproduce these images without permission.

Think this thread you're following right now, about the place of the 'human' when it comes to our spiralling collective additions to tech in all its forms, is really the key question right now. We should do something about it at Kendal this year, maybe a panel or a live interview or something.

100% Totally clarifies the point of being ‘out there’. Personally, I don’t go anywhere with out one and notepad and I adore maps. Probably forgotten how to,use a map and compass now, but I find the, so absorbing - a journey in themselves!