Experiments in deconvergence: it starts with a wristwatch and notepad

Simple first steps towards radically changing your life. Less time looking down, more time looking up.

For those who prefer to read on paper (or e-reader) rather than in your Substack or email app, I have converted this essay into an easily printable PDF file

Have you ever felt the ghostly tap of your phone in your pocket, only to activate the screen and see no notification there?

Have you ever felt the Pavlovian tug of it on your mind at some moment unbidden, even if the device is far from your conscious thoughts?

Have you ever wondered where all the time goes?

The good news is that there’s a path forward. In this new series on deconvergence, I’ll be outlining my own experiments in reducing the impact of my phone on my own life, and sharing the key tips that have helped me.

The deconvergence series to date:

An intrusive presence

In ‘Is the cyborg mountaineer still an artist?’ I set out my stance on a simple idea: that, when used without restriction, the smartphone is an intrusive presence in outdoor adventure. But let’s take this a step further. It is, to use Marshall McLuhan’s terminology, the ultimate hot medium. From

’s ‘Smartphones are hot’:To look into the screen of a smartphone is to be lost to the world. The gadget becomes an extension of the user but, more important, the user becomes an extension of the gadget. Like every hot medium, the smartphone isolates and fragments the self.

Or in my own words: it is the void.

If it were all bad then there would be no problem here. We could put it aside and get on with our lives. Addicts can get help breaking their addictions. But the thing about phones is that they’re really useful, and living without one in the 2020s is getting more and more difficult. This ultra-concentrated utility is one reason why they’re so ‘hot’.

What if it were possible to minimise the negative effects of the smartphone on the human mind without setting aside the essential utility?

The story of convergence – as it happened

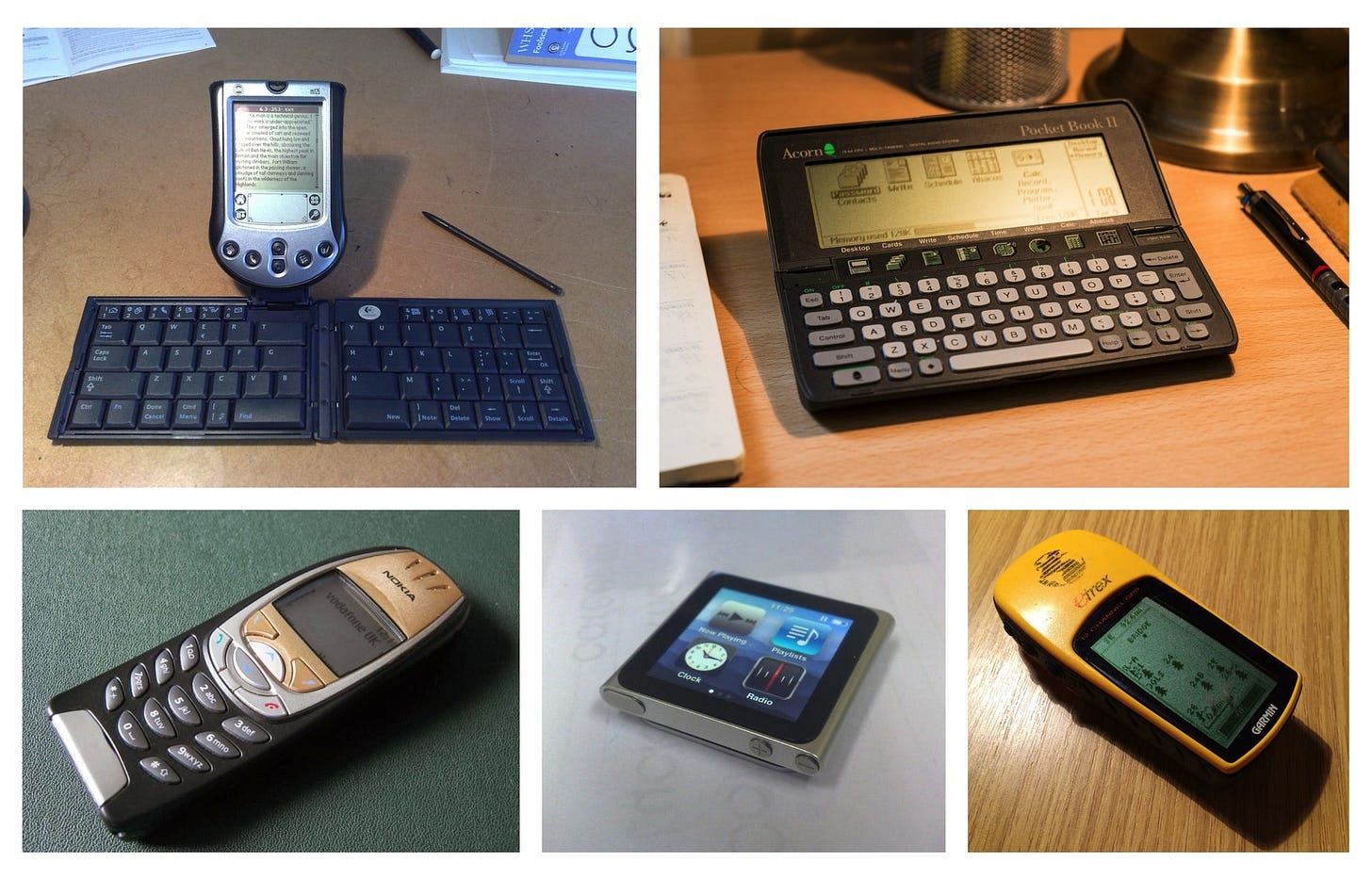

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, there was a lot of talk in computing science circles about convergence. This period happened to overlap with my compsci degree and years working in a phone shop, so I saw it happen in real time from several different perspectives.

More and more consumer gadgets combined features. At first this was gradual – a Palm Pilot with a camera, or one with an expansion slot so you could add GPS or a phone antenna. Back then, most people had a basic phone that could do nothing but call and send/receive texts, plus a separate CD or MP3 player. Sat-navs were common accessories for cars and handheld GPS was widespread in the mountains.

Although all these product categories survive in some form, for most people they have converged on the smartphone now.

By 2010, more and more people owned one, but they weren’t yet mainstream here in the UK. If you had a smartphone you were seen as a bit fancy. I remember the first person I ever met who owned one. It was 2008, and he was a fellow student on my degree course. He was mocked mercilessly for being a ‘rich boy’.

In 2011 I got a job at Carphone Warehouse, and the vast majority of phones people actually wanted to buy were cheap feature phones. But head office were pushing smartphones. Hard. Because they were more expensive and the margins were a lot more lucrative.

In 2011 the average phone sold at our store cost less than £100. How much is your current phone worth at RRP? The drive to adopt smartphones had nothing to do with progress and everything to do with profit. The game is over and consumers lost. We now live in a world where spending £600+ on a phone is the norm, and many people wouldn’t blink at £1,000.

By the time I left in 2014, more people were asking for smartphones – but many customers still asked for a basic phone first, and had to be reluctantly converted to buying a smartphone. It’s a fact that many people wanted smartphones because they’re useful, but both push and pull factors were at play. A massive advertising campaign was deployed nationwide to convince people to upgrade. Who can blame people for wanting the new shiny thing? Meanwhile at Carphone, we had brutal targets to hit and were given shady tactics to convince people to spend more than they intended.

I’m still haunted by this. It was not a job for me, and I got out as soon as I could.

But back then nobody knew what we know now. Nobody was talking about the negative effects of social media or the addictive nature of devices – and the square root of nobody was talking about the attention economy and technofeudalism.

More than a decade later, these subjects are mainstream and the world is a very different place.

Although the device itself isn’t at fault here – it’s more the incentives and business models of the attention economy – many of us have woken up to the idea that putting our entire lives into a single device may not be as great as we originally thought it was.

The thing about convergence is that a fully converged device is highly convenient. But with ultimate convenience we sometimes lose subtler qualities: intention, presence, deeper thinking. This may sound woolly, but on a long enough timescale nothing matters more. As years turn to decades, it becomes about your values and how you live your life.

The steps I’m proposing in this series all result in sacrificing convenience to varying degrees. But once you let go of the sacred cow of convenience, you’ll realise that it was never everything it’s cracked up to be anyway.

If you own a smartphone and have not already put measures in place to limit its impact on your life, it’s likely you have a screen addiction, whether or not you’re willing to admit it. The first step is to acknowledge this. The second step is to do something about it.

Deconvergence

Deconvergence is just like it sounds. Simpler, limited-use tools still exist, and incorporating some of them back into your life can reduce the negative impact of the smartphone by reducing your need for it.

It isn’t about completely ditching your phone, because for most people this is impractical. And would you even want to? As I mentioned earlier, smartphones took off at least in part because they are useful. From online banking to the ability to carry around a secure password database, smartphones have countless genuine benefits that I take advantage of every day. I don’t want to suggest for a minute that we should completely reject the technology.

I have experimented with going back to an old-fashioned dumbphone numerous times, most recently in 2024, but the world has moved on and it becomes harder to do every year. I don’t think I’ll try again.

Deconvergence is about diversity. It’s about spreading the load of tasks across a raft of simpler items instead of depending on your phone for every single thing in your life. It’s about choice rather than compulsion.

It’s about less time looking down and more time looking up.

The benefits compound with every small step you make. Many people are constantly glued to their phone because they unlock it to check the time, or look something up, and get sucked into a labyrinth of attention-grabbing notifications and apps. They did not intend to do this, but the technology has been carefully engineered to steal attention and time from you. Resisting these incentives is very difficult without a systematic approach.

Before you know it, 20 minutes or an hour have gone… and you’re not quite sure where. Can you even remember what you’ve been doing? You only unlocked your phone to check your messages! It’s a familiar feeling, isn’t it? Your time has been eaten. Your life has been eaten.

But taking small steps towards deconvergence can reduce the number of times you pick up your phone during the day, and therefore reduce your overall unintentional screen time. It’s as simple as that.

Step one: buy a watch

A 2023 survey indicated that average American smartphone owners checked their phones 144 times a day. How many of those pickups started with the need to check the time, then led to a spiral of unintentional use?

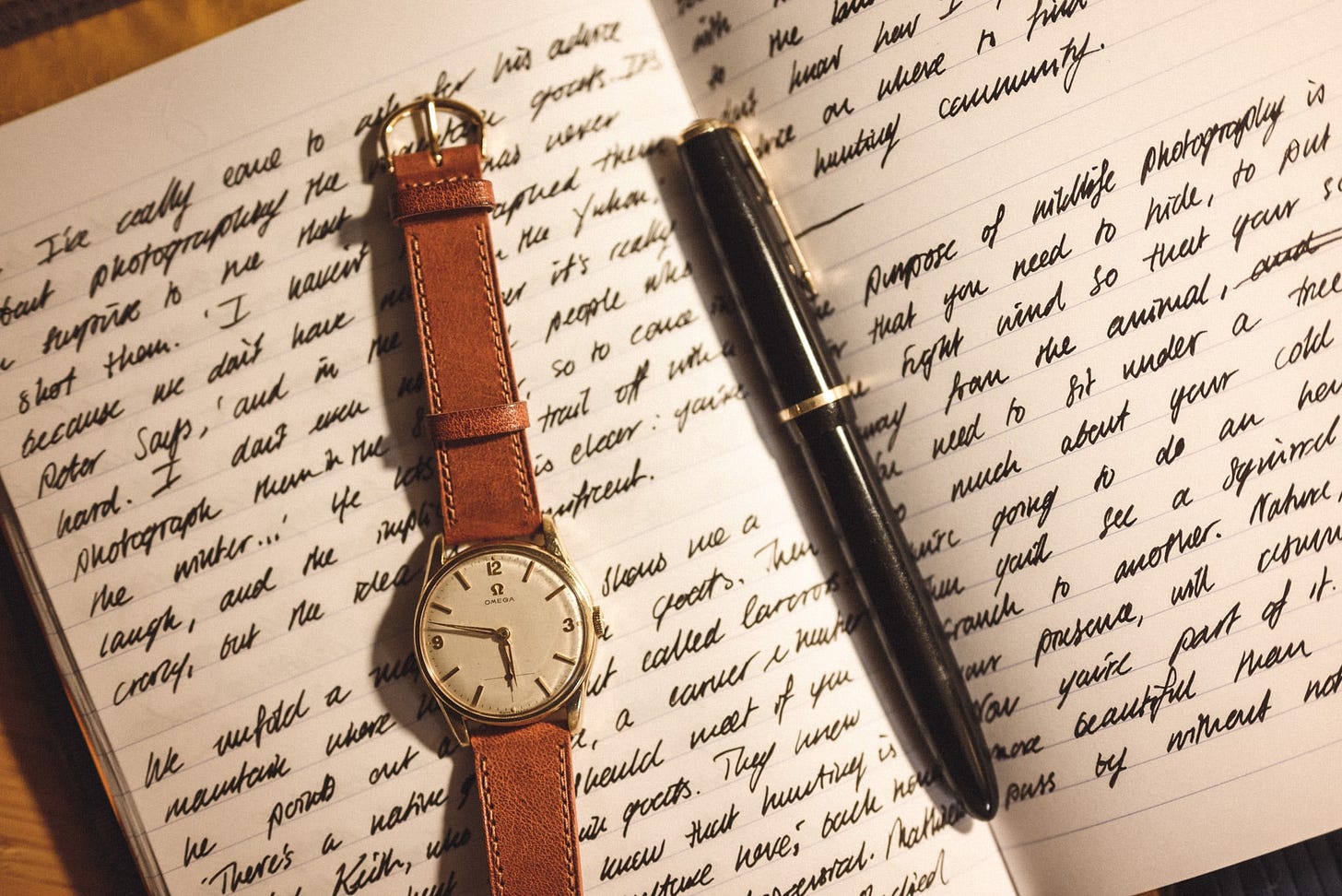

My own journey towards more a more intentional relationship with technology began in 2014 when I decided to buy a wristwatch again.

I hadn’t owned one for years. Even long before I owned a smartphone, a generic Nokia told the time perfectly well, so why would I need a watch? I got out of the habit, and anecdotally, based on the decline of watch wearing I saw amongst my friends and family members, a lot of other people did too back then.

I didn’t buy anything fancy. I think I spent about £7.99 on the cheapest Casio digital watch I could find, just like the one I’d worn as a child. (I wrote about this watch, or at least the one my dad wore in hospital in the last days of his life, in ‘The most important thing’).

The impact this watch had was enormous. If I wanted to know the time, I just looked at my watch instead of unlocking my phone. My number of phone pickups immediately declined, and although it did not solve the problem single-handedly by any means, it did create a foundation to build from.

It sounds obvious, but wearing a watch really is step one. Everything else follows from this. Trust me, it’ll change your life.

Beyond the functionality, wearing a watch makes a statement: I care about my attention. It’s a declaration of intent that you remember every single time you look down at your wrist and realise you have one fewer excuse to look at your phone. Yes, the luxury fashion world also tells people to buy (expensive) watches, but that’s not why you’re doing this, is it? You know the difference. That’s what counts.

More than a decade later, I still look down at my wrist multiple times a day and am reminded of this. It’s a permanent reminder of human values, of your commitment to slow time, like a memento mori.

What kind of watch to buy?

It genuinely doesn’t matter as long as it tells the time! But since we’re here…

If you want it to be, a wristwatch can also be a beautiful object in its own right and an expression of your personality. I’m not one to ascribe identity to material possessions, but if you care about things like the clothes you wear and how you decorate your house, I don’t think there’s anything to be ashamed about if certain types of watches attract you more than others.

You only really need one, but a case can be made for having an everyday watch and a dedicated ‘beater’ watch for adventures. Because I’m a nerd, I have four:

The heirloom. This was my dad’s watch, and my grandfather’s before him. It dates from 1961 and I inherited it in 2018. It’s very special to me but I don’t wear it every day. Because it’s serviced once a decade, it keeps perfect time. It bears its multiple lifetimes of service nobly; the scars on the crystal are from falls my dad took in the last years of his life.

A quartz field watch. I wear this on adventures. Literally any durable watch will do; many people will opt for something digital and rugged, but I prefer the aesthetics of an analogue field watch. And quartz is worry-free in the mountains. There’s nothing special about mine; it’s just the one I liked the look of that I could afford.

An everyday watch. In the mid-20th century most men had a watch like this. Small, likely stainless steel rather than gold, mechanical, not expensive or precious, and probably on a metal bracelet. This is my sweet spot. Going beyond pure utility or the sentimental attachment of a family heirloom, and lacking any status effects that a recognisably expensive modern watch like a Rolex might have, a watch like this makes a philosophical statement: that for as long as I wear it, I’m choosing pre-digital values in my life. Not for status among others but for what it represents to me.

My watch of choice in this category is a Lorier Falcon, a simple modern mechanical watch based on designs from the 1950s. I’ve had it for several years now. The watch is actually waterproof and quite capable on the hill. It may look dressy to modern eyes but in its native era it would have looked ordinary. The bracelet is actually an original new old stock 1950s beads of rice bracelet I found on eBay, but fits the Falcon quite well. If kept serviced, this watch will outlive me.

A vintage curiosity. I picked up this oddity for a song on eBay last year, described as new old stock from the 1940s. I took it to my local watchmaker, and after overhauling the movement he shook my hand and said he had never seen anything like it. It dates from 1940 and had likely never been worn. He speculated that it might be totally unique – a hand-made one-off. The movement is nothing special and it’s certainly not worth anything, but I think it’s beautiful. It came on a Bonklip bracelet of the type common in the 1930s but now almost impossible to obtain in pristine condition.

When I wear this watch, I feel an uncanny sense of being dislodged from time. There’s something hypnotic about being in the presence of an object that has taken the slow route through almost a century, bearing not a single trace of all those decades. If that’s not time travel I don’t honestly know what is. How is a miracle like this even possible? It’s the perfect antidote to your disposable smartphone, which zips through fast time and is obsolete in a few years, in landfill after a few more, dragging you along with it.

As you might be guessing, time is the point of all this.

The smartphone eats time, shortening our lives in every way that matters. A wristwatch gives it back. And perhaps a beautiful immortal wristwatch from another era reminds us that life is long after all if we just let it be. That we don’t have to live in fast time; that maybe we can take the slow road. That maybe some things last after all.

What about a GPS watch or smartwatch?

It’s better than your phone, but you’ll still be bombarded by notifications, your attention sucked towards a gazillion features – as well as another source of battery anxiety. Again, it’s about fundamental incentives. A mechanical watch, even a basic quartz watch, will accompany you for decades; a smartwatch will be technoscrap in a handful of years.

I’m not saying these devices should be totally avoided, but personally I no longer use them. For now, stick with a basic analogue or digital watch. I’ll have more to write about GPS in a future deconvergence entry.

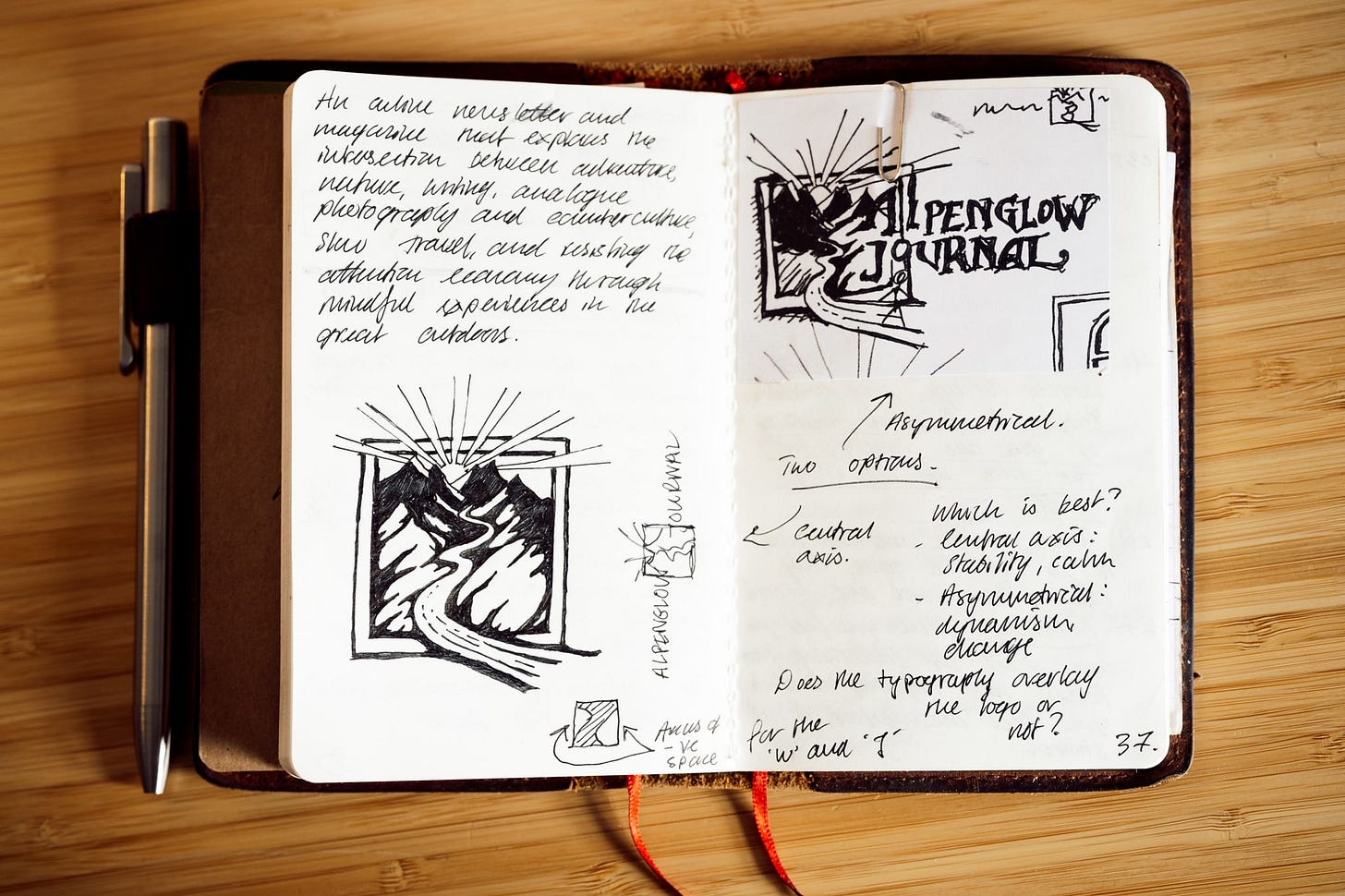

Step two: carry a notepad and pen

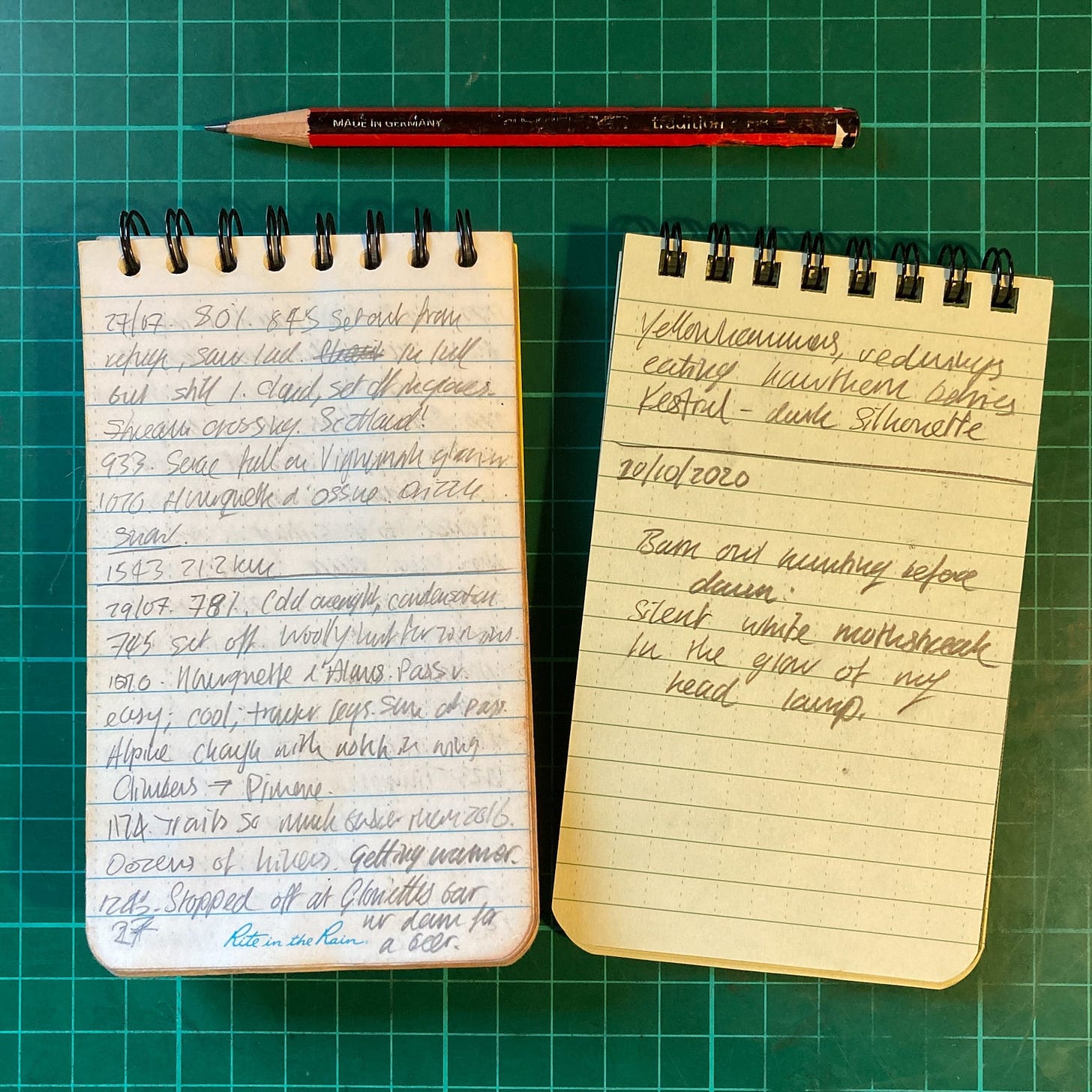

One of the basic utilities a smartphone offers is a way to record scraps of info: memos, ephemera, the little pieces of data we need as we go about our lives. The thoughts that come to us, the ideas we brew up and pop in the Notes app.

Buy a simple paper notepad and stick it in your pocket. Instead of entering these ideas and bits of information into your phone, write them down instead. Again, this sounds super simple but it’s actually a massive step.

It will feel alien at first. Exposing. You’ll fret that the information will somehow evaporate without the (fake) safety of the cloud. You’ll worry that you can’t carry enough information with you. As if you ever needed an entire library in your pocket anyway. But with time, as you realise that your true needs are a lot simpler and more limited than your phone told you they were, these worries will recede.

You’ll realise that a paper notepad is better than a smartphone in all the ways that matter. It’s a space that belongs to you and you alone, and its dimensions are human dimensions; it’s not a formless void that promises more than it can ever give, yet demands so much more. When you write in your notepad you remember what you have written, unlike the awkward autocorrected phrases your cramped thumbs negotiate with the glass. And it imposes no form on your thoughts.

At first your scrawls will be clumsy and faltering. Your hand will ache. But persevere. In a year, maybe two years, the idea of going back will be unthinkable.

In ten years, you’ll realise that paper is forever and that clouds are a lot less substantial than common wisdom would currently suggest.

A paper notepad is another fundamental step to freeing just a bit more of your mind from the glass cage. It’s another way to slow time the hell back down again and reclaim your life. It won’t change the world all by itself, but these small steps compound to create bigger positive changes.

What kind of notepad should I buy?

Again, it really does not matter! The cheapest spiral-bound pad from W.H. Smith will do the job just fine. But, once again, since we’re here…

I have a huge collection of notebooks and usually have five or six on the go at any one time, but the core notebook for me – the one that replaces my phone as a home for the ideas I have on the go – is my pocket notebook.

I bought a simple leather cover several years ago (this one). It can fit two pocket-sized notebooks inside. I added ribbons to act as bookmarks.

The notebooks are Lochby pocket-sized notebooks with plain paper. They’re similar to the popular Field Notes brand, but have more pages, are more sturdily constructed, and the paper is better quality. I fill five or six a year. Moleskine also make similar notebooks – they’re called Cahiers, and I used them for many years before I discovered Lochby.

In the field I also use small Rite in the Rain reporter notebooks, but the leather folio and twin Lochby notebooks is my core system.

I’ll write about my analogue writing systems in more detail in a future entry.

Next steps

Buying a watch and carrying a pocket notebook were the two first steps I made towards deconvergence more than a decade ago, and they’re also the most unshakeable. Other steps I’ll explore in future entries are more nuanced and challenging, but once you start wearing a watch again you won’t go back. Once you rediscover the sheer joy of writing on paper you won’t go back. You can only progress from here.

In future entries in this series, I’ll be taking a look at my experiments in deconverging other areas of smartphone use. Successes, failures, and everything in between.

Photography

Reading

Navigation, both in the mountains and everyday life

Public transport (timetables and tickets)

Task management and calendar

Communication

Music and entertainment

Focused writing and deep work

Deeper dives into focused analogue digital and analogue writing tools, as well as partial hardware alternatives to smartphones (this is where it really gets geeky)

Thanks for reading, and please subscribe to receive future entries in the series.

That’s all, folks

Images and words © Alex Roddie and James Roddie. No AI has been used in the creation of any work on this page. All Rights Reserved. Please don’t reproduce this material without permission.

Brilliant read and a topic I'm passionate about.

My biggest tip is to seek out a phone with a smaller screen. At some point the cheapest phones went from having smaller screens than the top models to larger and the reason is simple - big screens are more engaging.

I looked for a phone with full smartphone functionality but the smallest possible screen. For the past year I've been rocking a Blackview N6000 which has everything I need in a small form. It's less engaging, less tempting and more of a reassurance than a distraction. It also happens to be fully submersible, tough and have a battery that will last several days - perfect for my adventures.

Your watch tip is great, I've tried to explain this to friends so many times. I started wearing watches again about 3 years ago. I also stick to analogue (and quartz) as it helps me to visualise my time.

I love the notepad idea. I can imagine myself writing a list of all the things I wanted to google during the day, sitting down in the evening to review only to realise how pointless it all was.

What a great issue. I actually just got myself a watch after noticing that same effect of checking the time on my phone then loosing 30 minutes of my life. Thanks for the great story! Keep up the good work.